Matos uses adaptive techniques like contrasting colors on her catcher’s gear to overcome her vision challenges.

She has committed to play softball at St. John’s University and aims to win Gatorade Player of the Year.

Matos led her team to an 11-1 record and a No. 1 state ranking, recently pitching a two-hitter with 25 strikeouts in an 11-inning win.

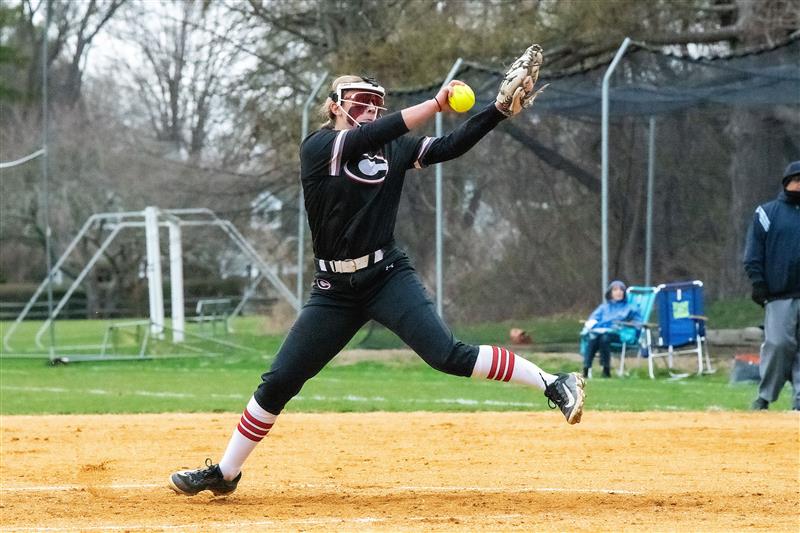

CHESHIRE, Conn. – As a Cheshire High School sophomore, Jenica Matos threw three no-hitters last season before the Rams squared off against their archrival, Southington High School, in a Connecticut Class LL State Championship semifinal game last June. One of those no-hitters came at the expense of the Blue Knights, so they were focused heading into the game, but Matos nearly repeated her performance, yielded just one hit while striking out 13 to help Cheshire win 4-0.

A few days later, Chesire lost the state championship game to Fairfield Ludlowe, 3-2 in 10 innings, but Matos sparkled again as she threw 191 pitches, allowed just three hits and recorded 16 strikeouts.

Not bad for a young woman who is legally blind.

A rare diagnosis

In 2018, after her 10-year-old daughter complained that her vision was fuzzy, Becky Matos took Jenica to a local eye doctor to have her vision checked. Nothing seemed out of the ordinary, but the doctor felt the girl needed glasses and fit her for them. However, as days and weeks passed, Becky Matos noticed her daughter was striking out a lot, and her maternal intuition told her something was wrong.

‘We took her back to the eye doctor, and this time the doctor was like, ‘Can I check the back of her eyes?” Becky Matos said. ‘We’re like, ‘Yeah, sure, do what you’ve got to do.”

The local eye doctor ran tests, got the results and sent them to doctors at nearby Yale New Haven Hospital for a second opinion. Henri Matos, Jenica’s father, got the call and immediately reached out to his wife.

‘He called me and said, ‘I need to take her to Yale, like, now. Today,” Becky Matos recalled.

After a battery of tests, doctors determined that Jenica Matos has a rare genetic disorder called Stargardt disease. It is linked to a mutation in the ABCA4 gene, which is responsible for making proteins that remove toxic substances from the retina. In people with Stargardt disease, fatty deposits and material form over time on a small part of the retina called the macula, which is used for sharp, central vision. As the deposits enlarge or grow in number, central vision gets blurrier, sensitivity to bright light often develops, and dark areas form in a person’s central vision.

There is no treatment or cure for Stargardt disease, and while estimates on the number of people in the United States who have it vary, according to the Cleveland Clinic, the number is between 30,000 and 200,000.

‘We left after everything and I went to my mom’s house and just broke down,’ Becky Matos said. ‘I was like, ‘I don’t know what to do.’ I came home and talked to Henri, and we just cried.’

‘It started getting blurrier when I was 11 or so,’ Jenica Matos said. ‘When I was maybe 13, I really couldn’t see. Since I was 13, I think it got like a little bit worse, but right now, it’s steady.’

Today, Matos is legally blind but does not see a world of black or total darkness. If you talk with her, she looks at you, but even faces across a kitchen table are somewhat blurry. She can’t clearly see someone standing 5 or 6 feet away, and while contact lenses help, they don’t fix the problem.

‘It just like, it goes from everything being blurry to being more clear, but if there is a sign somewhere, I can’t really read it,’ she explained. ‘But without them, everything just looks like a big blur and the colors kind of blend.’

Overcoming challenges

Matos turned 17 on April 17, but her vision will prevent her from ever having a driver’s license, and she can’t read the whiteboard at the front of the classroom. Her teachers often provide her with notes she can copy and study.

While Matos can’t see home plate when she is standing in the pitcher’s circle, she can find the strike zone with her fastball, which reaches speeds up to 64 mph. For context, that translates to a baseball pitcher throwing in the low 90s.

In addition to playing for Cheshire High School, Matos plays for a travel team, the Empire State Huskies 16U National, and has competed in events as far from New England as Colorado, Florida and Georgia. At 5 feet, 6 inches tall, she is not as physically imposing as some pitchers, but Matos is powerful and intense on the mound, with her sunglasses – which she wears rain or shine – giving her an imposing presence.

‘She’s a competitor, and she’s a thinking competitor,’ said Kristine Drust, Cheshire’s head softball coach. ‘She truly does seek out the game within the game to beat her opponents. When you see her, you will see that she is a gritty, gritty competitor.’

Drust said that while she and her coaching staff could make defensive accommodations for Matos’ vision, that hasn’t been necessary.

‘She’s a great defensive player, she really is, and I wish that we could all really understand what she sees and how she sees it. But she does, and she gets it done,’ Drust said. ‘We have never, ever found any holes in how she fields her position on the mound.’

Matos only needs two accommodations in order to pitch. First, her catcher needs to have a chest protector and glove that are in contrasting colors. To make sure that happens, the family bought a white chest protector and brings it to games because most catcher’s gloves are black or dark brown.

Last season, Cheshire’s catcher had a white chest protector and a white glove, which necessitated some creativity. ‘We colored in the webbing of her glove with a black Sharpie,’ Matos said.

The second thing Matos needs is a way to get pitching signals from her coaches. Ordinarily, catchers relay signals and information on what pitch to throw, but Matos can’t tell how many fingers her catcher may be flashing, so once again, Matos’s coaches have used some creativity.

‘Coach Kelly (Brenner-Hennessey, Cheshire’s pitching coach) also wears a black coat or black clothes, and she wears a neon winter glove,’ Drust said. ‘That’s how she signals the signs to the catcher and Jenica.’

Starting in January, when she plays for the Empire State Huskies, Matos and her coaches began using a high-tech watch.

‘It’s got a white screen with black lettering, and it’ll say like ‘FB Out’ for fastball outside,’ Jenica explained, gesturing that she needs to hold the watch close to her eyes to read the notes. ‘It’s kind of simple.’

Recruiting and college commitment

A high school sophomore who throws in the 60s, tosses three no-hitters and routinely collects double-digit strikeouts will get the attention of college softball coaches, but the Matos family was nervous about the recruiting process.

‘I was kind of concerned that, like, colleges wouldn’t look at me or take me because of (my condition),’ said Jenica Matos, who is now a junior. ‘At the same time, I kind of wanted them to know, rather than not know, because if they knew and they still contacted me, then I’d know that it wouldn’t bother them as much.’

Drust, on the other hand, saw the challenges Matos faces and her track record of success as a positive—something that could attract coaches.

‘I had concerns, but it was super important to get out to the public just how much success, even with some adversity, she was obtaining,’ Drust said. ‘In my conversations with the coaches that were recruiting her, that was a huge plus. Yes, she does have a disability, but to know how much grit, resiliency and success she has found. That is a player that every coach wants.’

It turns out Drust’s instincts were correct, and Matos had no reason to worry.

At midnight on Sept. 1, the moment college coaches could contact her, Matos started receiving text messages and emails.

‘She went from 8 a.m. on Sept. 1 until like 8 or 9 at night talking to college coaches,’ Becky Matos said.

After being contacted and visiting schools such as Seton Hall, the University of Massachusetts and other northeastern colleges, on Nov. 3, Matos announced her verbal commitment to play college softball at St. John’s University on X. Located on Long Island in Jamaica, New York, the Red Storm’s campus is less than 100 miles from Matos’ house.

‘I want my parents to be able to come and see my games,’ she said.

Looking ahead

For the last four years, Matos’ central vision has not deteriorated as quickly as it has for others diagnosed with Stargardt disease. She gets her eyes checked routinely, and while Stargardt disease typically does not lead to complete blindness, that does not provide much comfort.

‘I don’t know if I’m going lose my vision or not,’ she said, sitting at her family’s dinner table. ‘That’s kind of hard.’

Many things about Jenica Matos’s future are out of her control, but with the winter’s snow gone and her high school team’s season started, she is back in a place where she is in total control—the softball field.

‘I want to get the Gatorade Player of the Year award,’ she said, referring to an all-sport honor bestowed every year on one athlete in every state. As lofty as that goal may seem, it’s attainable. Matos was named to the Connecticut Class LL All-State team and was the Pitcher of the Year last season after posting a record of 21-2 while compiling 318 strikeouts in 156 2/3 innings.

As for her high school team, Matos wants the Rams to repeat as the Southern Connecticut Conference champions and win the state championship. Through April 29, the team was 11-1, with the lone loss to LaSalle Academy, a private school in Rhode Island. Cheshire is ranked No. 1 in the state.

On Monday, Cheshire defeated No. 4 Amity 1-0 in 11 innings, behind Matos’ two-hitter with 25 strikeouts.

‘Even though I have an eye disease, it doesn’t really shape who I am as a player and a person,’ Matos said. ‘It’s my talent and how hard I work. I don’t get anything given to me because I have an eye disease. I actually work for it, and I love doing what I do, even if it’s hard most of the time.’