Last week’s Republican National Convention was focused almost entirely on a different presidential contest than the one we see today. Speakers railed against President Biden, Donald Trump’s presumed opponent in November — but whose withdrawal Sunday rendered much of the criticism irrelevant.

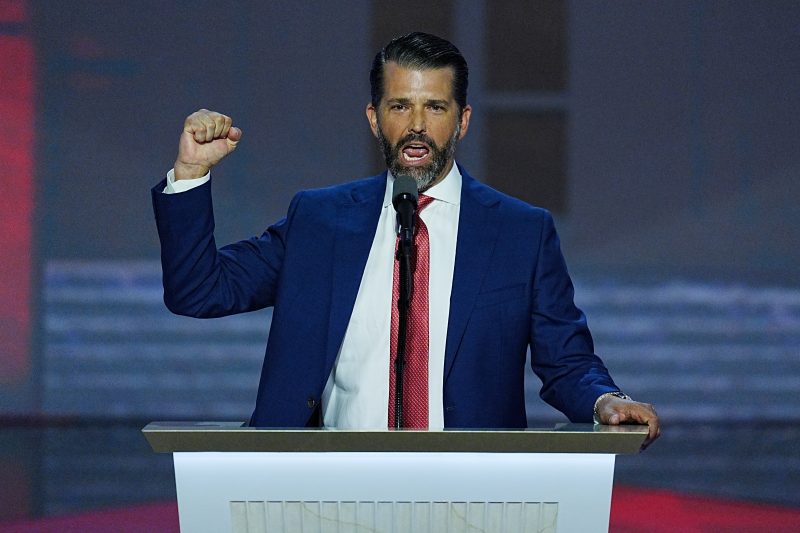

One comment made in a speech by the former president’s son Donald Trump Jr., though, targeted the Democratic Party more broadly.

“There was a time when the Democrats really wanted what was best for America, even if they had a different way of getting there,” he said. “It was the party of Franklin Roosevelt, John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King Jr. You may have disagreed with that party, but at least you could respect it.” He excoriated today’s “extreme Democrat Party” — a term that itself is part of a long-standing effort to indicate disrespect to the left.

That comment, though, made me wonder how views of the two major parties and views of their candidates have overlapped over time. Is it the case that, whether the party has changed, views of the parties and their candidates have? (It also made me wonder when Republicans like Trump Jr. became willing to cede MLK to their opponents, but that’s neither here nor there.)

To answer that question, I turned to data from the American National Election Studies (ANES). The ANES is a poll conducted around every presidential election and includes questions asking Americans to rate the political parties and their candidates on a scale from 0 to 100. The pollsters refer to this as a “thermometer,” with 0 indicating very cold opinions and 100 very warm.

As you might expect, views of the parties correlate to views of the parties’ candidates: If you like the Democratic Party, you tend to like the Democratic presidential candidates. If you don’t, you don’t.

What’s interesting in the data, though, is that only in recent years have views of the opposition party become more correlated to views of a party’s candidate.

Look at the box in the top left corner of the chart below. It shows views of the Republican Party from cold to warm (left to right) and views of the Democratic presidential candidate in 1980 from cold to warm (top to bottom).

Those with the coldest views of the GOP had warm views of the Democratic candidate. But otherwise, it’s a muddle.

Scroll down to the 2020 box at the bottom of that column, and you see that those with strong positive views of the GOP now have strong negative views of the Democrat in the race. The same holds for the third column: views of the Democratic Party vs. views of the Republican presidential candidate.

(The winning candidate in each election is outlined in black.)

In fact, 40 years ago, it was common for those viewing the Democratic or Republican party very warmly to also view the opposing party’s presidential candidate very warmly. In 1980, about a quarter of those who viewed either candidate very warmly also viewed the other party’s candidate very warmly.

In 2020, almost none did.

We can visualize that another way. Particularly since 2004, views of the opposing party’s candidate have plunged among those with strong positive feelings about a party.

This is in part because the number of people with positive views of the parties has also dropped. In 1980, only 6 percent of respondents rated the Democratic Party at or below a 24 on the 0-to-100 scale. Only 7 percent said the same of the Republican Party.

By 1996, that rose to 9 percent for the Democrats and 11 percent for the Republicans. By 2012, it was 19 percent and 25 percent respectively. In 2020, about a third of respondents rated each party that poorly.

It’s safe to assume, then, that part of the reason that partisan hostility to the opposing party’s candidate has increased among those with strong positive views of a party is that those with strong positive views of a party have eroded down to the most fervent partisans.

That’s who Trump Jr. was speaking to, of course: a Republican convention that had itself been winnowed down to its most pro-Trump element. In that room, it’s very safe to say, feelings about the Democratic Party’s nominee would run very cold indeed — whoever that nominee turns out to be.